1855 - 1905

Searching for a Cow

“It seemed as though everyone was always singing or whistling.”

That was Julia Donovan’s fondest memory of Northfield, where she lived all her life. Her stories go as far back as 1855, the year her dad Dennis, a native of Ireland, who fled the Irish potato famine, trundled in a coal wagon with his wife and five children through Chicago, and then headed north, following the Green Bay Trail up past Northwestern University, just opening its doors that year. They kept journeying north, to Winnetka, where the Chicago and Milwaukee Railway had just laid its tracks. From there, the Donovan family headed west a few miles, across a tangle of trees and undergrowth, crossing Skokie Swamp.

They had come to Northfield.

For thousands of years, Native Americans had called this region their home. When European settlers in the 1700s began exploring the area, which they described as a mosquito-infested swamp, it was populated by thousands of Potawatomi and Ojibwe Indians, part of the great Algonquin tribe. Under the terms of the 1933 Treaty of Chicago, ordering them to leave Illinois, their numbers dwindled as land grabs by settlers and the U.S. government forced them out. Among those exiled Native Americans was a Wisconsin chief named Wau Bun (meaning “the early light or dawn”) who reportedly camped in the area while traveling between Illinois and Wisconsin.

Taming the land

It was here, in this wild, unsettled scrub forest in the Illinois prairie, that Dennis Donovan made a clearing in the woods and built a log cabin, chinking the logs with mud. He had come because he could purchase land here, 80 acres, which he cleared by hand. His deed was signed by President James Polk, giving him “40 acres for half a hundred dollars”—or $1.25 an acre.

The land he settled is just east of where Bracken Lane is today, and south of Willow Road.

Donovan already had one neighbor to the east. A few years earlier, John Happ, a blacksmith, rolled into Northfield. He had immigrated to Winnetka in 1843 from Trier, Germany. He built a log cabin there and launched a thriving blacksmith shop to serve the smithy needs of settlers, along with stagecoaches and horses of travelers using the Green Bay Trail. His shop was a popular gathering spot for locals who stopped by to wait for mail and news from passing stagecoaches. But the new railroad extending along the North Shore, with a stop in Winnetka, threatened his business. So Happ sold his Winnetka land for $3 an acre and headed west in the early 1850’s to Northfield with his nine sons and a daughter. Here, he could buy cheaper land. The 120 acres he bought extended north from New Trier’s Northfield campus along what is now Happ and North Happ Road. Happ built his log cabin where the high school sits today. In addition to farming, he launched a new blacksmith shop.

Right after the Happ’s and Donovan’s came, a pair of young 15-year-old newlyweds arrived around 1860, staking their claim to 40 acres just west of the Donovan’s. Henry and Mary Brackendorf came with her mother, Mary Young. Bracken Lane is named after them. They were part of a wave of German immigrants fleeing overpopulation and strict inheritance laws. They too came to claim land on the Illinois prairie, and they would soon have four children, all born in their hand-hewn log cabin.

Another immigrant family from France, Constant and Marguerite Levernier, arrived in 1860. They were among John Happ’s first neighbors, and they bought 40 acres to farm along what is now North Happ Road. They came to Northfield with their son Alex, age 5. The Levernier’s paid $405 for their land at a “tax sale,” building a log cabin on what is now 663 Happ Road. Family lore is that they got the land by trading a horse and a cow.

Right after the Civil War, in 1866, the Seul family—Henry from Alsace-Lorraine France and Margarite from Trier, Germany—came to Northfield. They bought 48 acres along Winnetka Avenue and built their log cabin where 1970 Winnetka Road is today. They had 11 children.

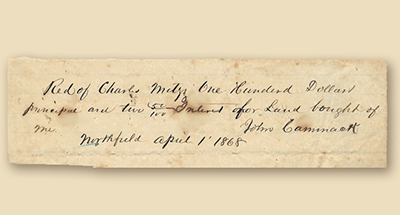

In 1868, another German immigrant family, the Metz’s, bought 13 acres to farm just north of the Donovan’s and Brackendorf’s, where Somerset Lane and Old Willow Road are today. They built their home on what is now 2211 Old Willow Road.

These were Northfield’s founders. As they struggled to tame the rugged prairie, nearby towns like Winnetka, Wilmette and Glencoe were already starting to incorporate, attracting business leaders lured by the railroad, who built luxurious homes as a pastoral retreat from the grime and stress of the city.

Northfield settlers were a world apart. They had their land, and each other.

Making ends meet

Dennis Donovan burned wood in a pit to make charcoal, a critical fuel source in those days. Using an ox team, he hauled the charcoal to Chicago to sell. He also worked as a laborer, measuring stone for the Sherman House, a big Chicago hotel. At home, he raised chickens and cows. His wife smoked a pipe.

Next door, the Brackendorf’s were pig farmers. Census data from 1860 shows the two families owned a combined 15 cows, seven hogs and a wagon apiece.

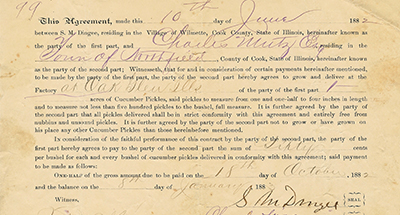

Across the street, the Metz’s tried pickle farming. Charles Metz had a contract guaranteeing him sixty cents for a bushel of 500 cucumbers “entirely free from nubbins and unsound pickles.” But that lasted just one year. The Metz’s also raised chickens and pigs and ran a truck farm.

For most Northfield families, the real crop of choice was horseradish–a stiff, tobacco-like plant that took painstaking work. Farmers had to crawl along the ground to uncover individual roots by hand, carefully stripping each plant of extra roots and eyes, except for the last eye, which they left in the ground to grow. As plants matured, farmers had to crouch and strip them down again. But horseradish cost nothing to produce, and labor wasn’t a problem. A farmer’s wife and children always helped. After harvesting the rigid leaves in the fall, families loaded the horseradish onto their wagons and hauled it to the city where they sold it by the pound to a processing plant. As one Northfield historian, Mary Hobart, observed, “Anything that could be grown (at) no expense and sold by the pound instead of the wagonload was a miracle crop.”

The Levernier family grew hay, which fed the horses, still the primary way people got around. They sold it for six cents a pound. Family members recalled putting up as much as 200 tons of hay each summer. Settlers loaded the hay on the back of their wagons and peddled it throughout Wilmette and Northbrook. Later generations hauled it to Rogers Park to sell to large stable owners. One grandson, Charles—when asked if he ever got to see a Cubs game–said “None of us ever went to a ballgame because teams played in the summer when we had to make hay.” The Levernier’s also raised potatoes and hogs. In the winter, residents of Winnetka would visit the Levernier farm to purchase a hog for butchering.

Packing hay was another profitable crop. Each fall, the Brackendorf boys headed to Skokie Swamp to collect it for free. They loaded their hay high on wagons and sold it to Chicago merchants who used it to ship goods like china and glassware.

The Seuls ran a truck farm, raising peas and vegetables, and they devoted five acres to horseradish. “That’s a devil of a thing to grow and take care of,” recalled Henry Seul, grandson of the founding family. In addition, the Seuls raised hogs and cattle, and grew their own wheat, which they took to a mill in Palatine to grind.

Truck farmers like the Metz’s and Seul’s peddled their crops at South Water Street, a wholesale produce market on the south side of the Chicago River’s main branch. It was a boisterous, chaotic scene, with truck farmers hauling their crates of local fresh fruits, vegetables and poultry each day to auction to local grocers and restaurants.

Besides farming, Henry Seul was elected the township’s first tax collector in 1881. He made his rounds on horseback with a heavy bag slung over his saddle, gold coins jingling as he approached each farm.

These were Northfield’s first settlers, and they took care of each other.

Hard times at home

After Mary Brackendorf and her husband Henry, a farmer, arrived in Northfield in 1860, they had four children: Peter, 1860, Lucy, 1862, Henry, 1864, and Julia, 1866. Then tragedy struck. The same year their youngest daughter was born, Henry died. He left his young wife with four children, all under six, plus an acre of cleared farmland, a one-room log cabin, an axe and a rifle.

Nearly ninety years later, Mary’s daughter Lucy, who never married and lived in Northfield all her life, told the Pioneer Press how her family survived with the help of Northfield’s founding families. She recalled how her neighbor Mrs. Henry Happ, among others, helped her mom raise all four kids, and eke out a living from the land. She remembered how her mother rigged up a calico curtain in their one-room cabin, so her two brothers could sleep on one side and the girls, their mom and grandmother on the other. Heat came from a wood stove, but the cabin never felt warm enough. For light, they lit candles.

To help her mom, Lucy took her first job at age 14 in Evanston, doing housework for $1 a week.

“My brothers had a horse that everyone kidded them about,” she said. “It had a stiff, straight neck, without any curve. But it pulled our wagon, and that’s what counted.”

To get to Lucy’s new job in Evanston, Mrs. Happ helped her gather all the bed clothes in the Brackendorf cabin, which they piled onto a tobaggan, and hitched to her family’s straight-neck horse. Then they snuggled under the bed clothes, making the journey on a cold February morning to and from Evanston. For three years, Lucy traveled back and forth, keeping house for the family. When they moved, she found another housekeeping job in Evanston and stayed six years. At age 23, she went to work for the John Quinlan family, prominent in real estate, and kept house for them for 12 years.

Tragedy and tumult

It was during her years with the Quinlan’s, when she was 25, that Lucy was plunged into a heartbreaking saga that would rock Northfield for decades and reveal the real character and camaraderie of its founding families.

It all began on a Sunday morning, September 11, 1887, when Margarite Seul and her husband Henry put on their black mourning clothes and hitched their horse to a lumber cart to travel in a funeral procession. The funeral was for a young farmhand from Evanston who worked for the Levernier’s. Families agreed to meet at the Levernier farm on North Happ Road with their wagons and horses, and then travel together to St. Joseph Church in Wilmette, where mass would be held. As the Seuls and other mourners lumbered in a single file along Happ Road, and then headed south and east to Illinois Road in Wilmette to reach the church, curious neighbors peered over their fences at the spectacle.

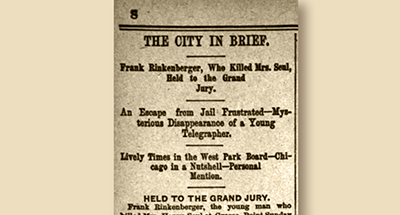

Among those neighbors were two 18-year-olds—Frank Rinkenberger and Fred Dahms. On this particular Sunday, they and several friends were tippling whiskey and beer, and entertaining themselves with Rickenberger’s Winchester rifle, taking turns shooting at a plug of tobacco on a nearby fence. Just as the Seuls’ lumber cart passed by, about 150 yards away, a chance bullet from Rickenberger’s gun struck Mrs, Seul in the back. She threw up her arms, exclaiming, “My God, I’m shot!” and fell dead in the arms of her husband. A local deputy sheriff, who was riding in the procession in a hearse with the body, saw the gun as he passed, and then heard the shot, followed by screams. As mourners quickly leaped from their wagons to confront the culprits, Rickenberger ran to the sheriff, and confessed he shot Mrs. Seul. He said it was an accident. He also said he was terrified of being lynched by the crowd, but did not try to escape. With some difficulty, the sheriff pulled Rickenberger and his friend away from angry onlookers and escorted them to a Wilmette jail.

One teenage friend at the scene, who saw the shooting, confirmed they had been imbibing that morning. Another friend said he warned the boys about recklessly using that rifle.

Once the suspects were in jail, irate Northfielders followed them there and swarmed the prison, forcing sheriffs to sneak them out of a rear door so they could spend the night at one of the officer’s local homes for safety.

Two days later, a deputy sheriff arrived in Northfield to assemble a jury to decide on the young suspect’s fate. Since Northfield had no name or identity, one Chicago paper described the scene as a “jury of the German residents of that vicinity” coming together. After listening to testimony, local jurors recommended Rickenberger be charged with death due to a gunshot wound. They asked that he be kept in custody to await the final decision of a Chicago Grand Jury.

Chicago Inter-Ocean, Sept. 13, 1887—A leading city newspaper reports on the killing of

Mrs. Henry (Marguerite) Seul, a Northfield pioneer.

The final verdict

Two months later, when the Chicago Grand Jury met, members spent seven hours deliberating, and then announced a verdict of “not guilty,” based on the fact that Rickenberger was shooting at a tobacco plug, not Mrs. Seul. It was an accident.

This enraged Northfielders.

But the character and connectedness of the town was on full display right after the shooting when Lucy Brackendorf immediately went home with Henry Seul to help care for his 11 motherless children. Lucy stayed on to help, and only returned to her job in Evanston once a family relative, Mrs. John Seul, was able to step in to replace her. But Northfielders never forgot the injustice. In 1973, grandson Henry Seul told the Pioneer Press about the “divine retribution” that finally came to Rinkenberger, who, according to Seul, “got in a fight while digging ditches, and the other fellow split his head wide open with a shovel.” With the help of neighbors, and the five oldest Seul daughters, who helped raise the younger kids, the family stayed and thrived in Northfield.

Sixty-two years after the tragedy, in 1949, the Seul name was widely known, but not for the shooting. That year, grandson Clarence Seul bought the last lot—now Orchard Road–being sold by a local farmer named Haut, and opened the popular Seuls Tavern in Northfield. Twenty-five years later, the Pioneer Press would observe, “the Seul enterprise on Orchard Lane in Northfield is as close to the village’s pulse as any gathering place in the area.”

Tough and determined

Young Lucy, in the meantime, grew up to be a force in Northfield. Her early setbacks gave her the tenacity and fortitude to take on anyone. And her family’s land gave her power. She kept her housekeeping job in Evanston until 1897. Then she returned to her family’s log cabin and spent the rest of her life there. In 1905, her living standards took a big leap when her bachelor brothers paid a carpenter $90 to build a proper home for her, just east of the Brackendorf log cabin. Twenty-two years later, in 1927, they remodeled that house again because their mother insisted. It still stands on 2284 Willow Road.

Lucy recalled her mom’s warning before she died in 1927: “Lucy, you’re not going to have anyone waiting on you the way you’ve been waiting on me. You better get this house fixed up so you can take care of yourself!” So, Lucy did. She spent the rest of her life in that remodeled home. In 1952 she told the Pioneer Press, “People always think because I’m single, I don’t like to tell my age. I’m 90 and I’m proud of it. I feel like I’m 16.”

Lucy’s friend and next-door neighbor Julia Donovan also spent her life in the same log cabin her dad built. Right after her family arrived in Northfield, Julia’s two brothers left, and spent four years fighting in the Civil War, coming home unscathed. Both settled in southern Illinois, leaving Julia to manage the family log cabin in Northfield. She lived there until she died at age 91. By the turn of the century, Julia was known as “Old Maid Donovan,” and notorious for owning a cow that liked to wander. She never had indoor plumbing, electricity or heat. She helped make ends meet by boarding the local schoolteacher.

And she never had the luxury of attending a nearby school. “Getting an education (in Northfield) was a problem in many ways,” she told the Chicago Daily News in 1937.

Julia had to walk or ride in the family wagon each day five miles to Wilmette, where St. Joseph’s Church had a school on Lake Avenue. Other Northfield children traveled to Northbrook. “Snows were terrible then,” Julia said, recalling how she and classmates walked over the crusted snowdrifts that covered the crabapple trees.

Over in Winnetka, the community elected its first school board in 1859 and hired its first teacher for $20 a month. They also set up a budget: $17 to rent a school building, $13 to buy a stove, and $5.75 for a Webster dictionary. That same year, back in Northfield, young Julia was turning age seven, and ready to learn to read.

But it took Northfield another 33 years to build a school, and 65 years to organize its own school board.

A hike to the outhouse

The first sign that a school might be built in Northfield was a deed filed by the Chicago Title Company in 1878. John Brown, a farmer who lived where Sunset Ridge Country Club stands today, donated a quarter of an acre of his land on the corner of Sunset Ridge and Willow roads. Neighbors thought his generosity stemmed from his own frustration at hauling his school-age kids to Northbrook and Wilmette.

It took until 1892 for Northfield’s first school, named after John Brown, to open. It was a small, one-room brick schoolhouse serving about 20 students, with no plumbing or electricity, an outhouse, and a potbellied stove for heat.

The little Brown School was part of District 5 until 1903. Then the county renamed it District 29. But nothing else changed. The county ran the school, using Northfield tax dollars. There was no school board, and no local control.

At the same time, New Trier High School opened its doors to its first 76 students in 1901, and soon become the first American high school to feature an indoor swimming pool. Over in Winnetka, the teaching methods of Carlton Washburne, an education reformer who arrived in 1919 to oversee its schools, put Winnetka’s pedagogy on the map.

And in Kenilworth, the Rugby School, a fee-based private school for boys with a Harvard-trained headmaster, opened in 1891, boasting strong ties to the University of Chicago. That same year, Kenilworth Hall opened for girls, led by a headmistress well-versed in Latin, French, math, history and literature. When architect George Maher was enlisted to design a new public school for the community, the prospectus assured Kenilworth parents it “embodies the best results for lighting, heating and ventilating.”

Back in Northfield, “that outhouse felt like it was a quarter-mile away,” recalled Alex Levernier, a grandson of the settlers who was one of the first to attend the new school.

“Brown School was kind of a shack,” recalled Richard Burmeister, a native Northfielder whose dad owned a farm on the corner of Sunset Ridge and Happ roads, stretching all the way to where Edens Highway is today. He said his dad pulled him out of Brown School in the 1920’s so he could attend a more progressive school in Northbrook.

“We’d all sit together in one room,” Burmeister recalled. “And I can remember one kid—the class pest—who would lean out of his seat when the teacher wasn’t looking and stick his fingers up his nose, making the most awful faces. I’m 86, and I still remember it like yesterday.”

Alex Levernier remembered walking each day to the little Brown school from his family’s farmhouse on North Happ Road. As he walked, he would pass the log cabins of Northfield’s pioneer families, along with acres of open land.

There was still no town, and only about 12 to 14 farm families calling Northfield home.

He would pass the Metz’s farm, renowned for its vibrant flower gardens; and he often greeted Lucy Brackendorf and Julia Donovan, who knew everyone, and welcomed any kids who stopped by.

“Old Maid Donovan, who lived next door to the Brackendorf’s, had this cow that sometimes wandered off,” he said. “I used to hunt it down after school with my friends.”

He also remembered how Julia Donovan’s dark little log cabin was neat as a pin. And how his schoolteacher always lived at Donovan’s.

“But it’s the cow I remember most,” Levernier said. “It would wander through the forest and swamps between Winnetka Avenue and Willow Road with a bell around its neck. We kids were always looking for that cow.”