Northfield, 1905-1926

What? Wau Bun?

It’s 1905, and everywhere you look, there’s change.

In Glenview and Shermerville (later to be Northbrook), teams of horses are hauling in the first gas, electric and telephone lines. To the east, Winnetka has been lighting homes for five years with the new Municipal Electric Utility plant. Profits from the plant help pay for the town’s teachers. Residents are getting clean water through a water tower the village has built at the foot of Tower Road. Phone service is just now being brought into homes.

And Northfield? Nothing is happening. It’s a 3.23 square-mile rural “no-man’s land,” sandwiched between a half-dozen booming North Shore towns. It has no downtown. No stores. No village. The local school is a one-room shanty. Money is tight for the dozen or so founding farm families who live here. Life’s a struggle, but Northfielders are proud of the land they own, and each other.

Still, they’re outliers, always looking for ways to make do. And that’s the legacy and culture of Northfield through much of the early 1900’s.

Nothing will really happen here for another 21 years.

A push for power lines

In the case of electric power, it takes a hard-driving Chicago businessman, Syles Fralick, who owns a sprawling farmhouse at 1930 Sunset Ridge Road, to put up his own money to get the first power lines installed.

Appalled at not having the same conveniences as other towns, Fralick in the early 1920’s puts up several thousand dollars to string a few utility lines to serve the scattered farms spanning Sunset Ridge and Happ roads.

“I remember Fralick convincing my dad to chip in some money to help,” recalls longtime Northfielder Richard Burmeister, whose dad owned a farm on the corner of Sunset Ridge and Happ roads. “Fralick told us, ‘Once those farmers try milking cows by lightbulb rather than lantern, we'll get our investment back.'” And they did, according to Burmeister—within six months.

But victories like this are a drop in the bucket next to the rapid advancements in other communities. Northfield stands still.

And local farmers must find clever ways to survive.

While other incorporated communities focus on using local tax dollars to pave and improve roads, Northfield farmers struggle just to pay their taxes. So, they devise a scheme to keep up with the dreaded tax collector, who visits each local farm by horse and buggy, gold coins jingling.

The farmers decide to gather with their wagons and horses at Wagner Farm, where they are allowed to haul away 10 to15 tons of gravel, depending on the size of their tax bill. Traveling along the township’s dirt roads, they use the gravel to fill potholes. The result? The county gets free upkeep for its roads, and Northfield farmers get credit for paying their tax bill in full.

It's a win, but they are still an anomaly among neighboring towns, and they keep falling further behind.

Winnetkans like this rugged little town to the west with its rolling hills and undeveloped land. It amuses them when they drive through Northfield to buy produce from a local truck farm or a hog for butchering and spot the funny red hand-pump on the corner of Sunset Ridge and Willow roads, next to Brown School. There is no piped-in water here, so the hand-pump (which remained on that corner through the 1950s) draws water from a well to fortify local school kids.

And more out-of-towners are driving through Northfield. Equestrians from nearby communities love its picturesque remoteness. It’s a stunning sight to watch riders in their brilliant red coats gallop across the Brackendorf and Metz farmland with their horses in pursuit of the fox.

True to Northfield’s spirit of survival, the Brackendorf’s build a thriving business boarding and caring for horses whose owners from nearby towns like to ride on their land.

There is also the sticky problem of golf. As Northfield historian Mary Hobart observed, “Winnetkans wanted a place to play golf—and they were tired of waiting for someone to die so they could get into Indian Hill Club.”

Gold standard for golf

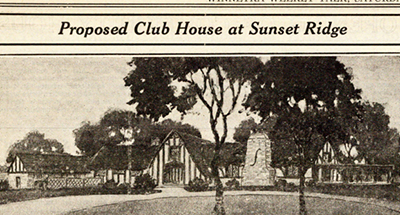

Land to build Sunset Ridge Country Club—property once owned by John Brown, who donated the land to build Brown School—is purchased by ten thirtysomething Winnetka families in 1922.

Two years later, club membership is full, reaching 250. Finances are robust. The first golf foursome tees off on Independence Day on the stunning championship course. A new, rambling timber and stucco clubhouse opens, boasting “all modern conveniences necessary to complete a first-class club.” The building’s main feature, according to the club, is the men’s locker room, designed with “excellent ventilation” and “light in every corner of the room.”

Meanwhile, just one-third of a mile south down Sunset Ridge Road, the 13 boys and 5 girls attending Northfield’s one-room Brown School still use an outhouse with no electricity or plumbing, like so many other local families.

The community can boast of some advances: on April 12, 1924, Northfielders vote to make District 29 a local school district, meaning for the first time they can run their own school, and elect their own three-member school board. But nothing else changes. Farmers refuse to pay a penny more in taxes.

Northfield also gets a store. Alex Levernier, one of the first kids to attend Brown School, opens a grocery, located where Northfield’s library and post office are today. When Prohibition is repealed in 1933, it also becomes a tavern.

Still, life in other towns keeps advancing. Life in Northfield feels more like a step back in time.

It takes a seismic personality to finally shake the little community out of its inertia—a man indeed larger than life.

His name is Samuel Insull, and just one month after Northfielders finally mobilize to form their own town—on October 23, 1926—naming it Wau Bun, Insull is on the November cover of Time magazine.

He knows every U.S. president from William McKinley to Herbert Hoover, although he finds them all boring, except Teddy Roosevelt. His exploits, according to Orson Welles, help inspire the 1941 film, Citizen Kane. Insull is the biggest name in the global electric utility industry, and a household name in Chicago.

Around 1926, he sets his sights on Northfield.

It might have surprised local farmers that Insull’s early years weren’t much different than theirs.

Business mogul eyes Northfield

Born in London in 1859, Insull was forced to go to work at age 14 when his father lost his job. He never stopped working. His first job as an office boy for a real estate firm paid him the equivalent of $1.25 a week—the cost of a railway ticket and lunch—so Insull walked to work each day and skipped lunch. He was ambitious, hard-working and curious. He mastered every entry-level task he could in whatever low-paying jobs he managed to land spanning real estate, finance and publishing.

As a teenager, Insull met P.T. Barnum, and they stayed friends for life. But his real idol was an American inventor, albeit eccentric genius: Thomas Edison. Insull became obsessed, and he plunged into learning everything he could about Edison. He got a lucky break when an American banker who was Edison’s representative in London needed a secretary. At age 19, Insull went to work for him, quickly impressing his new boss with his command of all things Edison. Three years later, in 1881, the great inventor and father of electricity—who was chronically disorganized—lost his personal secretary, and 21-year-old Insull set his sights on coming to America to work for Edison in New York. Insull had also been offered a far more lucrative opportunity at a New York brokerage firm, but without even knowing what salary Edison would pay, he turned the financial firm down. He wanted to serve the great inventor.

When they first met, Edison was shocked at Insull’s youth. But he quickly saw his value. The young man proved his prowess at finance, marketing, sales and engineering. He could also organize his boss and always find his umbrella. The two worked together for 11 years. By the time Edison consolidated many of his companies in 1889 into the Edison General Electric Company, Insull was a vice president. Three years later—in a new era of monopolies—Edison’s company merged with a rival, forming General Electric. Insull was offered a lucrative position as vice president. He turned it down. He thought he deserved to be president, so he quit, and struck out on his own. He moved to the one city he and Edison believed to be the biggest growth market in the electric utility industry: Chicago.

Insull quickly took a job as president of Chicago Edison—for just one-third the salary he could have made at General Electric—and began acquiring firms. His goal was simple: be the innovative leader in delivering electricity to homes, businesses and railroads. In 1907, he became president of Commonwealth Edison, expanding his empire from downtown Chicago to the entire country. By 1910, at age 50, he was the undisputed leader of the American electric utility industry, and one of America’s richest men.

He was also now married, with a son, and discovering the charms of rural living not far from Northfield.

He bought 4,000 acres of farmland in Libertyville, and built an Italianate manor, known today as the Cuneo mansion. He brought in the North Shore Line railroad; and he bought land, on which he built and sold homes. He also helped build a school, a hospital and a golf course. He brought in electricity. Soon Libertyville was known as a “one-man town.”

And here’s what the world was learning about Insull: he could never stop thinking big or tinkering with the details of everything he touched. He also cherished his British roots.

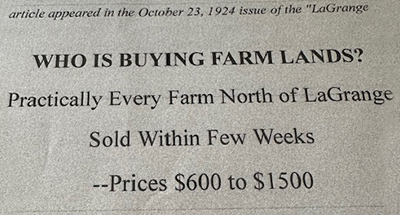

He found another easy mark in 1924 to conquer—this time, 2,200 acres of rural farmland owned by German farmers, 13 miles west of the Chicago Loop. He went a step further this time, and formed his own real estate firm, the Metropolitan Real Estate Company. He also named the town, which he envisioned as a quaint English community, much like his homeland. He called it Westchester.

Long-lost cousin: Westchester

He gave the streets Old English names—Chaucer, Dickens, Kipling and Shakespeare—and he brought in its first rapid transit line, opened on October 1, 1926, to connect the new village with the city of Chicago, allowing prospective buyers to easily visit.

And he did it all in secret. Farmers were offered as much as three times the real value of their land, and deals had to close in one day. “The farmers do not know the purchaser…. the whole affair is surrounded by much mystery,” said the LaGrange Citizen in 1924. “In all cases, the farmers were paid half-cash, and the deals were closed within a few hours after they agreed upon his price.”

Insull’s team moved fast. They oversaw the construction of 42 miles of paved streets, 84 miles of sidewalks, 28 miles of storm sewers, 24 miles of sanitary sewers and 600 streetlamps. They laid 34 miles of water mains, bringing in water from Lake Michigan, and planted 15,000 Elm trees.

“I know of no place where such great progress has been made in so short a time,” said contractor Charles Wiegel, who oversaw sidewalks, to the Westchester Tribune in 1926. “I wonder if the public really recognizes just what great activity is taking place.”

They built hundreds of bungalows, two-flat buildings and apartments crafted from brick, stucco and hand-hewn timbers, giving Westchester a look distinctive from any other Chicago suburb. Land was donated for a civic center, and for schools, too.

Population forecasts for the 3.7-square-mile town—just a little larger than Northfield— were 98,000.

Insull may have hidden behind the scenes, but he had a front man: George F. Nixon. Nobody ever saw Insull, but everybody saw Nixon.

Real estate A-listers in the 1920’s called Westchester a “wonder suburb,” and Nixon led the charge.

“Westchester is a beautiful garden community where millions of dollars have been lavished in the creation of a perfect paradise for home-seekers,” said The Greater Chicago Magazine in June 1929, praising “…the great accomplishments made by George F. Nixon and Company and the many other groups sanctioned in the rebuilding of this magnificent ‘made-to-order’ city…”

“I do not believe any one of us can grasp the development that will take place in Westchester in the next decade. Fortunes will be made there….” added developer William Zelosky to the Westchester Tribune in September 1926.

And nobody lived larger than Nixon.

“(The) George F. Nixon organization bestrides the real estate world of Chicago like a Colossus,” said The Greater Chicago Magazine in 1929. Over the course of his life, Nixon bought and sold more than 5,000 acres of fully developed land in the greater Chicago area. He led local real estate associations such as the Chicago Real Estate Board and the Illinois Association of Real Estate Boards, and was the first president of the Metropolitan Chicago Home Builders Association.

He even had a school named after him in Westchester, the George F. Nixon school, on land he donated. It opened in 1931 and still stands.

What really set Nixon apart was his flair and salesmanship.

He was born to a middle-class family in Chicago in 1892, the son of a salesman, the eldest of five. In 1913, he launched his career as a realtor, builder and developer. By his late 20’s, he was flying high.

In 1925, during his campaign to sell Westchester, he spent $400,000 on a mansion for his family in Glenview, the magnificent Colvin Chateau, set on 160 rolling acres. Built by financier William H. Colvin, the estate was “one of the finest on the North Shore,” according to the Cook County Herald, and “a source of inspiration for amateur and professional painters who on summer days set up their easels along Glenview Road and is a delightful scene for thousands of motorists.”

Nixon planned to live large in the chateau, and then subdivide the bulk of the acreage into upscale homes, “a character of property seldom put on the market,” according to the Cook County Herald. Buyers would be near a new train line just being built by Insull. Electricity, landscaping, sidewalks and streets were all part of the package.

While Nixon was luring the “common man” to Westchester, he saw Glenview as an aspirational community touting luxurious homes and a lifestyle to match. And he set the tone.

Three months after buying the chateau, he invited 100 guests to his estate to watch the famed Olympian, film star and championship swimmer Johnny Weissmuller—also his houseguest for several days—show off his skills in Nixon’s outdoor pool. Nixon made sure that Weissmuller told the Chicago Daily Herald how “deeply impressed” he was with Nixon’s plan for Glenview, and “indicated a desire to buy a homesite where he could install a good-sized swimming pool for summer training.”

By 1929, Nixon also owned a penthouse at the Edgewater Beach Apartments on 5555 N. Sheridan Road, built “as an upscale alternative to huge mansions for Chicago’s wealthy elite.” He also owned the Nixon Building at Clark and Monroe, headquarters for the George F. Nixon & Co.

He was the proud leader of the “Nixon Producer’s Club.” At a dinner to honor his top salesmen in 1929, Nixon’s honorees were joined in a group photo by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, the “champions of all champions,” noted The Greater Chicago Magazine. That same year, Nixon’s top salesmen embarked on a series of airplane trips to leading cities around the country to stay on top of trends. “Never before in the history of Chicago has anything of this nature been undertaken,” said The Greater Chicago Magazine. Nixon’s goal, of course, was to make sure his salesmen “were thoroughly trained in the science of real estate merchandising.”

All soon be unleashed on the farm families in Northfield.

A new grand plan

Insull and Nixon saw their Westchester experiment as a grand success. By 1926, with the Westchester electric line carrying 530 riders daily and home sales surging—making Westchester one of the fastest-growing Midwest communities—they cast about for other opportunities.

And nothing whetted their appetite—or appealed to their greed—quite like the remote, unincorporated community without a name just to the east of Nixon’s dream town of Glenview.

In fact, it was almost too good to be true.

Here, among the North Shore’s most promising suburbs, was a backwoods little bog so far behind everyone else, and so ripe for the picking. They could hardly contain themselves. What worked in Westchester could easily work here. So, they forged ahead. This time, they would bring even more muscle and moxie to their plan.

They bought 700 acres, about one-square mile, under the name United Realty Company, extending north from Glenview Road through Northfield. Land cost them $86,000. Insull—who by now owned nearly every Chicago electric railroad—built a new train line, too, to the tune of $10,000,000.

“We have made this big investment, secure in our confidence that this region is destined to become one of Chicago’s most beautiful and desirable suburban residential districts,” said Britton Budd—Insull’s right-hand man on rapid transit–to the Winnetka Talk in 1926.

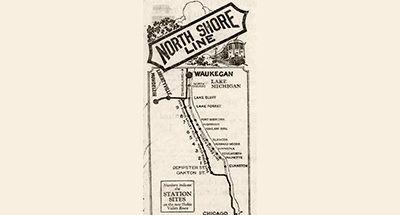

The new train connected with the popular Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad—known as the North Shore Line—which traveled from Chicago’s Loop to serve Evanston, Wilmette, Kenilworth, Winnetka and Glencoe, on up to Waukegan. But this new, 25-mile extension—called the Skokie Valley Route of the North Shore Line—cut off at Howard Street, then ran west and north, parallel to U.S. Route 41, serving commuters at nine new stops in Glenview, Northfield, Northbrook, Highland Park, Lake Bluff, and Lake Forest.

Construction of the track began in June 1925. Service began a year later. True to Insull’s vision, new high-speed, electrically operated trains began to draw a new wave of suburban homebuyers able to quickly travel to and from the Chicago Loop.

Communities served by the North Shore Line’s new Skokie Valley Route got a boost, too.

Each stop got a fancy train station. Evanston architect Arthur U. Berger, best known for his transit station designs—many now recognized by the National Register of Historic Places—was hired by Insull to create identical stations at all nine stops. Each had Spanish Colonial architecture with stucco walls and red-tiled roofs, and were equipped with modern-day lighting and plumbing. Stations were designed, “to harmonize with the residences of the North Shore district through which the line passes.”

A top-notch train

That might have been a stretch for Northfield.

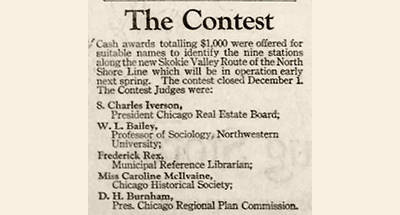

In fact, among the six communities where the new train stopped, Northfield was the only train stop without an incorporated town or identity. What to call its station? Insull knew a good promotion opportunity when he saw it. True to his P.T. Barnum pedigree, he held a contest, “Name-the-Station,” for each of the nine stops along the Skokie Valley Route. He offered $1,000 in cash prizes.

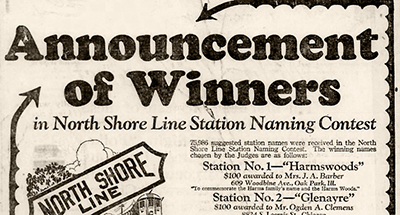

He appointed a panel of five judges prominent in civic affairs, among them the president of the Chicago Real Estate Board; a Northwestern University sociology professor; and the president of the Chicago Regional Plan Commission, who also happened to be Daniel Burnham’s son, D.H. Burnham, a Glenview resident. It was their job to select “the nine most appropriate names.” They got 75,000 entries. Nine winners were announced and split the cash. Each was publicly recognized in their local newspaper for submitting a top-ranked name.

It wasn’t too much of a stretch to understand the names that won in Glenview, Northbrook, Highland Park and Lake Forest.

“Harmswoods” (south Glenview)—submitted by Mrs. J.A. Barber, Oak Park: To commemorate the Harms family’s name and the Harms Woods.

“Glenayre” (north Glenview)—submitted by Mr. Ogden A. Clemens, Chicago: Glen may be associated with the Glenview Road, or the town of Glenview that is just west. The name is attractive yet simple, not easily confused, yet easy to remember and spell.

“Northbrook” (Northbrook)—submitted by the Northbrook Civic Assn: Northbrook is the logical name because the station will be in Northbrook township, the same township in which the established and progressive Village of Northbrook is located.

“Briergate” (south Highland Park)—submitted by Bessie R. Alexander, Evanston: It is appropriate because of the beautiful golf course nearby. All of the people living in this community are familiar with this location as near Briergate Golf Club. In fact, this club has been instrumental in helping build up this community.

“Highmoor” (north Highland Park)—submitted by Mrs. Gertrude C. Crane, Morton Grove: Representative of woodland beauty and variety of landscape descriptive of the vicinity which is so reminiscent of the Scottish Moors.

“Sheridan Elms” (south Lake Forest)—submitted Mrs. Belle Falwell, Milwaukee: The name combines in association Fort Sheridan and Old Elm Road. It has an old-world sound possessing the charm and simplicity which are so representative of this suburban locality and also typifies the sedate architecture which characterizes this vicinity.

“Skokie Manor” (north Lake Forest)—submitted by Miss Dorothy Shandberg, Chicago: It is the head of the Skokie Valley, famed for its beautiful estates and forests with beautiful vistas and picturesque scenery.

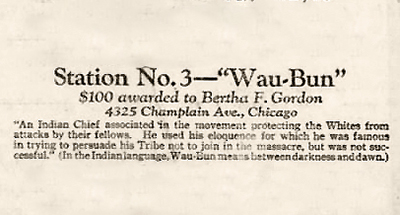

And Wau Bun? Among the 75,000 entrants was a Bertha F. Gordon, who lived on Chicago’s south side, at 4325 S. Champlain Avenue, about 26 miles from Northfield. It’s unlikely Bertha ever stepped foot in the area before the arrival of the train or knew anything about the community.

But the story of the massacre that took place on this former prairie where the new train would now run was compelling. It had been beautifully captured in a popular book (still in print), Wau Bun: The ‘Early Day’ in the Northwest, published in 1856 by Juliette Kinzie. This gripping saga of the prairie homeland that Native American tribes—led and inspired by chief Wau Bun—loved, and his bravery and resilience amidst the trauma and suffering of his people, could well have captured Bertha’s imagination, too.

So, she entered the name, and this was her reason for submitting it:

Wau Bun: An Indian Chief associated in the movement protecting the Whites from attacks by their fellows. He used the eloquence for which he was famous in trying to persuade his Tribe not to join in the massacre but was not successful. (In the Indian language Wau-Bun means between darkness and dawn.)

Bertha won $100 and got her name in the newspaper. Insull’s panel assigned the name to Northfield.

Why Wau Bun?

The lesson for locals? “Wau Bun” might be what happens when a little town has no ambiance, no architecture, no stunning vistas and no name. It’s hard to know exactly how Northfielders felt about it. On the one hand, their modern train station represented progress. Their town finally was on the map, and farmers didn’t have to pay a dime.

But speaking quietly among themselves, it must have rankled longtime Northfielders who saw no connection between the new name and the community they loved. Yes, Indian tribes had lived here and loved the land. But what about Northfield?

Just a few decades earlier, all the unincorporated towns in Northfield Township had called themselves “Northfield.” Parts of Glenview were “south Northfield” and “west Northfield.” Northbrook was “north Northfield.” Slowly, as these towns incorporated and adopted their own names, only one “Northfield” was left: the little 3.2 square-mile town to the east. The name stuck. But now, in the spirit of always making do, locals accepted this unexpected “Wau Bun,” bequeathed on them by Samuel Insull, along with his behind-the-scenes prodding to finally form a Village.

There was one more change that unsettled locals. About this same time, George Nixon built new real estate headquarters in Northfield, right in the heart of downtown, near where Walgreen’s is located today. Chicago’s “Colossus of real estate” was now on the scene. Farmers spotted him everywhere.

What to do? By now, the dozens of landowners scattered throughout the Village represented second and third-generation families. Land was selling for sums they could have never imagined. They were sitting on a bounty. Was this a bad thing? Maybe this was how they got ahead.

They stayed quiet about Wau Bun.

Standing Our Ground—Alex Levernier (pictured with his wife Mary Barbara Happ) came to Northfield in 1860 at age five with his immigrant parents. His son, Alex, born in 1888, ran the town’s general store and was a Village trustee. Their family was skeptical of outsiders like George Nixon and Samuel Insull coming into Northfield. But not everyone agreed.