1926

A Test for Our Town

It’s 1926, and everything in Northfield is unfolding according to plan—at least, in the eyes of two larger-than-life business titans who plan to reap big winnings.

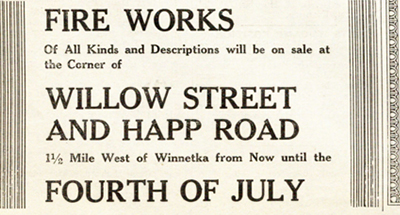

A new elegant train station has just been built with a brand new sign proclaiming “Wau Bun.” It stands near the southwest corner of Happ and Willow, right next to Northfield’s best answer to a community center: Al Levernier’s general store and coal yard.

There’s also lots of talk about forming a village. Most locals agree: it’s time.

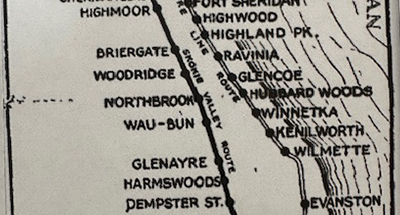

After all, just to the east, Winnetka, Glencoe and Kenilworth have a 57-year jump on Northfield, each becoming a village in 1869. Wilmette became official in 1872; Glenview in 1899; Northbrook in 1901.

Why the lag in Northfield?

For starters, who’s going to run the town? And, will farmers agree to do the unthinkable—pay more taxes?

As Northfield wrangles over the complexities of becoming a village, Glencoe and Winnetka are showcasing to the state of Illinois—and later, the nation—a first-of-its-kind approach to running local government. Glencoe is the trailblazer, and Winnetka quickly follows in 1915, pioneering a new “council-manager” form of government, which puts all policy-making power in the hands of six elected village trustees and an elected village president, who then appoint a village manager to serve as chief administrative officer of the village.

By 1926, Winnetka is thriving under this “council-manager” system, attracting top talent to help run its town. Its first village manager, Robert L. Fitzgerald, comes equipped with a mechanical engineering degree from Purdue, and has worked as an engineer for the state of Wisconsin before coming to Winnetka, where his primary job is to oversee the water and electric plants owned by the village. When he is drafted to serve in World War I, Winnetka welcomes Herbert L. Woolhiser, educated with both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering from the Univ. of Wisconsin. One of his first jobs is to build the town’s stately Georgian Revival limestone Village Hall, dedicated in 1926.

Attracting such top-tier talent, or planning a grand municipal building, are not in the cards for Northfield. With no water, electricity or phone service, it is still decades behind other North Shore towns.

Who is going to get Northfield out of its rural rut?

Two men, boldly waiting in the wings: Samuel Insull, the world’s electricity king, and president of Commonwealth Edison; and George Nixon, Chicago’s real estate Colossus.

Scheming to rescue Northfield

By now, Insull was the worldwide leader of the electric utilities industry. “He loved the role of being a big business leader. He had achieved tremendous success. There seemed to be no stopping him,” said Harold Platt, Loyola University history professor in a 2002 interview with PBS. “I think (Insull) sees that he can do no wrong….that use of electric power would just get larger and larger, so why not control more and more of this economic growth and have it all under his own control?”

Insull was also the business equivalent of The Wizard of Oz. He was seen by few, but always working diligently behind-the-scenes. Geoge Nixon, on the other hand, was the quintessential Professor Harold Hill from The Music Man, always stepping out in front of everyone, and selling a dream.

Between the two of them, they had an answer to every problem—as long as it profited them. And, for awhile, Northfielders gave them free reign.

In fact, Northfield became a village in 1926 because Insull and Nixon needed it to happen. They had already bestowed the town with its new name, Wau Bun. Insull had built the train station and was providing electricity for the trains. They both owned prime acreage all over town. They also had a comprehensive plan for how to sell Northfield, based on their recent success in the western suburb of Westchester, where they had turned farmland into a full-fledged town. They had even hand-picked its name. Now, they were moving full-tilt on their next project, developing rural acreage in Glenview (where Nixon owned a $400,000 mansion) for aspirational, discriminating, high-end homeowners. And Northfield? It was their most tantalizing target of all. It offered an alternative. Here, they could sell the North Shore to the masses at dirt-cheap prices. With Nixon’s real estate offices now located smack in the center of town, they moved full-speed-ahead to make Wau Bun official.

And Northfield farm families watched it all unfold.

What a sight it must have been in 1926 for local farmers to spot Insull the way the whole world saw him: driving around their town in a huge, black, chauffeur-driven limousine, bearing the demeanor of an English-country gentleman, inspecting the progress of a village he wanted to transform from farmland to a modern community with quaint Gaelic gabled homes, and street names reminiscent of his London childhood: Dickens (19th century English novelist); Bosworth (15th century Battleground in the War of the Roses); Eaton (an Anglo-Saxon settlement by a river); Graemere (bucolic village in the English Lake District); and Churchill (renowned British statesman and historian).

From farmland to the future

Clarence Seul, grandson of Northfield pioneer Henry Seul, remembered: “Insull was a great man at the time,” said Seul to the Winnetka Talk in 1974, decades after his family sold land to Insull in the 1920’s. “He bought up a couple hundred acres where Bess Hardware is now. He put in sidewalks. The whole town thought highly of him.”

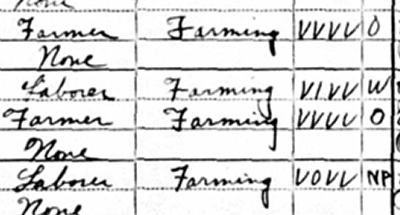

Northfield’s population by 1926 was about 230, and this was the era of big business growth in America. The heroes of the day were successful titans of industry like Henry Ford, J.P. Morgan and—to the immense pride of Chicagoans—Samuel Insull. Every other town on the North Shore was attracting the era’s business visionaries and the promising innovations they spawned. And Northfield? Even by 1930, census data shows family after family living along Happ, Willow, Sunset Ridge and Wagner roads with the same symbol: “F” for farmer.

Change would be hard. Northfield’s rural roots and tight-knit social network ran deep.

As Henry Seul, another grandson of the pioneer Seul family, told the Winnetka Talk in 1951, the big social event at the time was the “threshing bee,” when neighbors and friends came together after a grain harvest to help with the painstaking job of separating the edible grain from the straw. Families would gather at each other’s farms to help, and it was the social happening in Northfield.

“There’d always be a big dinner during the day,” Seul recalled. “All the neighborhood menfolk would come in from the fields to tables set up in the yard. All the women would be there, helping out, the sisters setting the table.’

In the afternoon shade, he added, the tables would groan with large cuts of ham and beef, preserves, fresh corn, home-churned butter, fresh-from-the-oven bread, and pots of steaming coffee. The men were tanned and sweaty, Seul recalled, and the girls were pretty and fresh in their crisp crinolines, while their mothers bustled around in the kitchen, dreaming up ways to outdo their neighbors when it came time to thresh grain on their farm.

House parties and barn dances were also common, and adults played pinochle and euchre by the hour.

Rustic pastimes like these may have isolated Northfielders from their more sophisticated North Shore neighbors, but locals were content.

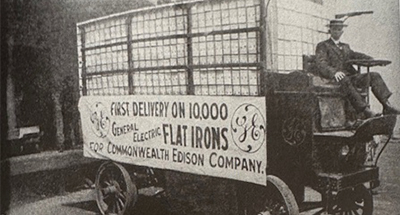

There was one way Samuel Insull did help local farm families profit from the big business surge exploding around them. He had pioneered a landmark idea, sending salesmen door-to-door to sell his company’s stocks and bonds, and giving away free appliances. “It was quite unusual in the 1920’s for ordinary Americans to own stock,” said Loyola history professor Harold Platt, citing Insull as the only business bigwig who brought the world of corporate ownership to the most remote neighborhoods—like Northfield.

Bringing big business to the farmers

The idea began when Insull, an Englishman, spoke boldly around 1916 about America’s need to prepare for World War I. Already acclaimed as a marketing genius, Insull was appointed by the Illinois governor to launch a campaign to sell war bonds door-to-door throughout the state to help pay for the war. His effort was such a success, he decided to keep it going. This time, however, he sent his sales team door-to-door to sell utility stocks and bonds from his own power company. He also tried to get American housewives—especially those in remote areas—hooked on appliances like electric toasters and irons, thus connecting them to the power grid. At one point, he gave away 10,000 electric irons to homeowners willing to sign up as new utility customers.

With Insull’s reputation around Northfield as a charming, kindly, man-of-the people, it’s likely his carefully groomed door-to-door salesmen enchanted local farmer’s wives. After all, it was a rare moment when the modern world came to them, and promised to ease the burden of daily life.

Elizabeth Levernier, who married into the Constant Levernier family, one of Northfield’s pioneers on Happ Road, was a fan of Insull’s in the 1920’s, and she bought into his promises. Forty years later, she lamented to this author about the money she lost buying bonds from him.

In an interview in 1967, Levernier still bitterly remembered the $800 she invested with Insull in the mid-1920’s, and was never repaid. But when she bought them, she was uplifted like everyone else by his promises.

While Insull and his sales team got a thumbs-up from Northfielders like Levernier and Seul, rumors about Winnetka were creating some worrisome buzz.

Clarence Seul was age 18, and working his first job at Levernier’s grocery store and coal yard, when the grapevine began to hum in 1926 with talk about Winnetka, and he shared his memories in 1974 with the Winnetka Talk: “Northfield was all farmland,” Seul recalled. “Then in 1926, we heard that Winnetka was going to incorporate this territory, so we got together and incorporated as the town of Wau Bun. There were about 12 farms, and the farmers didn’t want to go into Winnetka. That is how it all began.”

A Turning-Point for Our Town

Did Winnetka really have its eye on acquiring Northfield? Or did Insull and Nixon fuel those rumors?

No newspapers from the day mention any advances from Winnetka. What they do talk about is Northfield’s real estate frenzy.

“The United Realty Company already has subdivided into residence lots the 120 acres lying…north of Willow Road, where it also maintains a large real estate office for the sale and further development of its holdings,” said the Winnetka Talk in 1926.

Indeed, any visitor passing through Northfield wouldn’t only be impressed by the gleaming train station, linking locals to downtown. What really defined Northfield was George Nixon’s aggressive and imposing real estate activity.

Just two years later, the Winnetka Talk would describe both Nixon’s and Insull’s impact on Northfield: “…where two or three years ago, there was only farm acreage. Today, it is covered throughout with white and red corner stakes, marking future home sites, and still larger white and red stakes bearing the names of streets and avenues…”

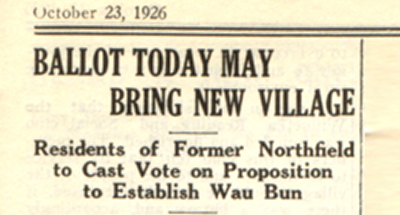

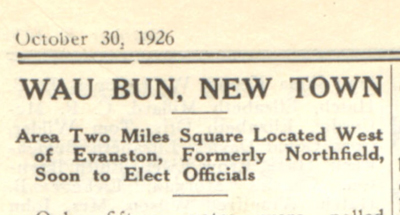

A lot of lofty promises had to be made in 1926 to reassure buyers about this budding territory. With Nixon leading the charge, and a new train station proclaiming “Wau Bun,” locals scrambled to rouse enough voters on October 23, 1926, to make things official.

Henry Seul, whose father was a member of the first village board, told the Winnetka Talk in 1973 that townfolk had to get creative with the village boundaries to legitimately form a town. With a population of about 230, Northfield had to quickly boost its numbers. “They wouldn’t have (become a village) if they hadn’t included the people south of Winnetka Avenue,” he said. “You see that funny dip on the Northfield map? They had to have at least 250 people to incorporate, and wouldn’t have made it otherwise.”

No doubt George Nixon, a Glenview resident, helped mastermind some of the finer points of incorporating. Nixon was always one step ahead.

A Win for Wau Bun

As for getting out the vote, other communities like Northbrook, Glenview, Winnetka and Wilmette had, since the turn-of-the-century, depended on local newspapers to inform voters on municipal issues. Northfield had no such luxury. Formal notices had to be posted in the window of Al Levernier’s store and coal yard, and on two utility poles: one on the corner of Willow and Happ, just north of Al’s store, and the other due south, on the corner of Happ and Winnetka Avenue.

With no municipal polling place, locals voted at Al’s store. Polls opened at 6 a.m. and closed at 4 p.m.

“Today will determine the fulfillment or disappointment of a dream,” said the Winnetka Talk, describing Wau Bun as the “…Winnetka west area, a hamlet two miles square with the Willow street station on the Skokie Valley line of the new electric road as the center. For many years, this crossing of the North Western railroad company was known as Northfield, the only semblance of a station being a long side track and a name.

“Today,” the Winnetka Talk added, “may mark another important epoch in the history of the Happ and Willow road crossing where, only a comparatively few years ago, the original owner of all the land thereabouts purchased it for $6 an acre. Some of those areas, it is said, sold more than a year ago for $4,000 an acre, and are today being sold out in small lots at so much per front foot, as the inevitable progress of the new section, destined to become a two-mile square village of homes, churches, schools, stores and other business enterprises, goes steadily onward.”

Such rhapsodic sentiments ended with a reminder that the “streets, drainage and forestry committee of the Village council of Winnetka” would perform its due diligence “to determine if Winnetka is in any way affected by the proposed new village at its west door.”

The vote that day was decisive. Wau Bun became a village on October 23, 1926, by a margin of 63 to 15. Two months later, Northfield elected its first board of six trustees and a president, following Winnetka’s “council-manager” model. Thirty-eight people voted at Al’s store to elect John Happ, grandson of the early settler, who ran unopposed, as president. Trustees were Alex Levernier, John Seul, George Selzer, Pete Selzer, Leo Retzsinger and William Boetsch. Al Kotz was elected clerk and Bernard Schildgen, police magistrate. The town’s fiscal budget was $5,000.

Watching it all was George Nixon. He had a grand plan for Wau Bun. So did Samuel Insull.

Just one week after the December election, the Winnetka Talk described the challenge posed by the ever-constant presence of Insull and Nixon. “The large sale of vacant property in and around the new village, both lots and acreage, which, it is said, are soon to come in for various forms of improvement, will be among the first problems to come before the new Village board at its future meetings.”

It would take just months for that issue to split the board into two rancorous factions. And just as fast, the name Wau Bun began to wear thin, too.

A hot contest

Northfield lore has always been that trustees met at Al’s store. Board minutes tell a different story. In fact, trustees met each month at the United Realty Company, George Nixon’s firm which, minutes say, was “used by the Village as a Municipal Building.” From day one, Nixon kept a tight rein on the board.

Another myth is that the uncontested December election produced a peaceable, cohesive board for the first two years. In fact, the December election was just a placeholder. The following April, Wau Bun held its first contested election to choose a president for two years, along with six trustees who would cast lots to determine which three would serve for one year, and who would serve for two-year terms.

What followed as a torrid election, and a side of this peaceful, bucolic farm community no one had ever seen. Suddenly, Wau Bun became a hotbed of discord.

“The older villages along the North Shore have nothing on the newest village in the township, Wau Bun, in the way of staging a red-hot political fight at the annual village election,” said the Winnetka Talk in April 1927. “Wau Bun…situated on Willow Road west of Winnetka where its broad acres for generations have produced corn and ‘spuds, and are now staked off in town lots by a subdivider, is rapidly taking on ‘city airs’….Thus, wide and varying differences of opinion have arisen among members of the official family as to how the details of the future course of the growing Wau Bun should be conducted.”

It all came down to this: on one side was Citizen’s ticket, led by John Happ, who was proudly born on Happ Road in a log cabin in Northfield in 1868, and a farmer his whole life. On the other side was the People’s party, led by Bernard Schildgen. He was also humbly born in a log cabin in Northfield, this time on the eastern end of town in 1866. He too was a lifelong farmer.

Happ campaigned on a platform of “ultra-conservative improvement and development.” What did that mean? According to Elizabeth Levernier, who lived in Northfield at the time of the election—and spoke with the author in an interview in 1967–Happ had a solid relationship with Insull. Their properties were in close proximity, and he could have well sold land to him. Happ was also more open to Nixon’s vision, along with Insull’s, to use their leverage to transform Northfield into a model town.

Schildgen, whose party’s motto was “to run the town right,” owned acreage on the east side of town, close to Hibbard Road, and did not embrace the two zealous outsiders.

No apathy in Wau Bun

In a concerted effort to get out the vote, each party borrowed a proven campaign tactic from Winnetka: they drove voters to the polls.

“Workers in both parties were in the field early, and with cars appropriately labeled, just like they do in the neighboring villages to the east, rushed frantically hither and yon over the country roads throughout the Wau Bun area, determined that no one eligible to vote should be permitted to stay at home,” said the Winnetka Talk about election day. “And only two escaped, so thoroughly was this canvass made.”

Of the 125 locals registered to vote, 123 went to the polls. “Near 100% Ballot,” the Winnetka Talk headline read. Something had been unleashed.

The vote was close. Happ won a two-year term in April 1927 by six votes, and he brought four new trustees who aligned with his more relaxed, open attitude toward Insull and Nixon. The opposing party’s Schildgen would eventually lead the village for eight years after Nixon and Insull finally lost their grip on Northfield. But that was still years away.

As for the name Wau Bun, it took only eight months for villagers to rise up in unison and scrap it.

It had never felt right. But there had been so much fanfare around Insull’s new train station, locals had kept quiet. At the very first board meeting on Dec. 15, 1926, the first item of business was the question of “retaining the name of Wau Bun.” A vote was taken, and trustees voted unanimously to keep the name.

Things changed the following April, after voters went to the polls to support their combative candidates. They were stakeholders now. They had a voice, and they were learning to navigate this new world of politics. Perhaps lack of education and rural isolation had stymied their confidence, while they watched bold outsiders step in and take charge. But now they felt bold. Wau Bun was their town, and they didn’t like the name.

No doubt Nixon hated it too. For buyers seeking an upscale North Shore address, the name was a mismatch; and it sure looked awkward in his ads. He got some help one day from a disgruntled local, which Northfielder Mary Hobart described in her 1961 study, Northfield—A Friendly History.

Hobart’s story sets the scene: “Mr. Insull was riding in the front car (of his train) to view with pride the latest addition to his empire. With him stood a real estate promoter, Mr. George Nixon… As the train approached Northfield, Mr. Insull noticed with horror that someone had crossed out the word “Wau” on the sign of his new station and had put “Hot,” so the station name read “Hot Bun.” Mr. Insull was outraged, but Mr. Nixon calmed him down, and promised he would do all in his power to have the name changed.”

A Sign of Change

Nixon knew just what to do next. Amidst the furor, he circulated a petition around town. It was presented at a packed board meeting on June 15, 1927, with 67 signatures, the required half of Wau Bun’s 125 registered voters. Locals that evening flocked to Nixon’s realty office—and its official municipal meeting room—to show their support. At every step, Nixon stood with them to help navigate the legal hurdles.

“Northfield—which until now has only meant the name of one of the townships in northern Cook County—is receiving a lot of advertising upon the part of a large Chicago subdivider, and that advertising leads to a desire upon the part of some citizens to change the name of the village of Wau Bun to the Village of Northfield,” said the Daily Herald in June 1927, noting that a petition had been presented, and trustees would meet the following month to consider a name change.

The business of banishing the name Wau Bun forever was successfully accomplished at a board meeting on July 7th, with the Secretary of State acknowledging that Northfield’s petition was legit, and no other town in the state bore its name. So it was settled—but not before some wrangling.

“It is said that several new names for the village were considered, including the name ‘Skokie,’ after the great swamp to the east,” wrote Mary Hobart in Northfield—A Friendly History. (At the time, the Village of Skokie was called Niles Center, and it did not change its name until 1940.)

“Mr. Nixon would have none of it,” Hobart wrote, “because his interests dictated that a name with any flood association was too dangerous for real estate values. He had enough trouble with the flash floods of the Middlefork of the North Branch of the Chicago River. ‘Sunset Ridge’ was also suggested, and when rejected was used to rename Kotz Road. ‘Northfield,’ the name of the longstanding Township (which also caused much confusion), designated our location in relation to Chicago, and above all was completely without any swamp connotation.”

Pioneer settler Julia Donovan, born in 1850, was still living during that election in her family’s hand-hewn log cabin on Willow Road. She always remembered people calling her and family members the “river folk,” because they had to cross Skokie Swamp to get anywhere. But being called a ‘Northfielder’ also suited her, and everyone else, just fine.

And quickly, locals turned their attention to the serious business of running a village. While neighboring towns embraced seasoned, sophisticated engineers to guide their future, we had farmers at the helm.